Benefits Cliff Employer Pilot Program Evaluation

Overview and Strategies for Employers

October 2024 | White Paper

Executive Summary

Overview

The “Great Resignation” of 2021 brought public awareness to the challenges that employees and employers face when it comes to workforce retention in the modern world. One cause of workforce turnover is when low-wage employees face a benefits cliff. A benefits cliff occurs when “an increase in someone’s pay triggers a greater loss in public assistance” (Goodwill Industries of the Southern Piedmont, n.d.). Often, pay raises are not sufficient to make up for this loss and families are left without the means necessary for their basic needs like housing, food, and childcare.

Fear of losing public benefits (such as subsidized childcare or income-based housing) can trigger a resignation or keep individuals from accepting more work hours, pay raises, or promotions (Roll, 2018; Ruder & Terry, 2024).

In response to the benefits cliffs issue, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta designed the CLIFF tools (Atlanta Fed, n.d.-b; Ruder & Terry, 2024). CLIFF stands for Career Ladder Identifier and Financial Forecaster. The tools provide useful information to low-wage earners and those facing benefits cliffs so that they can make informed financial and career decisions.

The Benefit Cliff Employer Pilot program (the Pilot program) was developed in response to the growing awareness among employers of the detrimental effects of the benefits cliff for low-wage earners, their families, and employers themselves. The Pilot program examines the financial implications of wage increases and seeks innovative solutions to lessen the impact of the benefits cliff on economic growth and mobility for lower-wage earners. The Pilot took place between 2023 and 2024 across four employer sites: Goodwill Industries of the Southern Piedmont (GISP), Goodwill of North Georgia (GNG), Atrium Health (Atrium), and the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta (Atlanta Federal Reserve). Participating employers developed activities to implement the CLIFF tools among employees and job seekers. Three sites conducted one-on-one CLIFF coaching sessions with employers and job seekers. These sessions utilized the CLIFF tools most applicable to participants and provided information and resources to lessen the impacts of the benefits cliff. All Pilot sites used the CLIFF tools developed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta to guide counseling and education efforts.

The UNC Charlotte Urban Institute conducted a program evaluation to document the pilot activities and outcomes among the four employer sites. The evaluation also highlights the benefit-cliff experience and areas where employers can provide support. The key findings and recommendations from the evaluation are shared below.

Findings

A total of 172 employees and job seekers participated in at least one CLIFF coaching session as part of the Pilot. Most were female without dependents and employed full-time. Participants’ incomes were below the Living Income Standard (NC Budget & Tax Center) (median income was $33,397).

- Around 40% of employees and job seekers had personally experienced the benefits cliff due to annual pay raises, promotions, or employment changes. The benefits most commonly impacted were SNAP/WIC (i.e., food stamps), rental assistance (e.g., housing choice vouchers, income-based public housing), earned income tax credits (EITC), and healthcare assistance (e.g., Medicaid, subsidies).

- Despite losing public assistance benefits and gaining higher expenses, most participants would still accept a promotion or raise. Participants valued self-sufficiency and income over public assistance.

- Certain lower-wage workers are falling through the cracks. The evaluation found that most Pilot participants have incomes that are lower than what they need to meet basic needs yet are often just above the limits to qualify for public assistance programs. In the Pilot, those most often in this circumstance were full-time employees. This implies that benefits cliff interventions are most critical when low-wage employees are considering a pay raise, promotion, or increase in hours.

What support did participants receive from the Pilot?

- Employed and unemployed participants came to CLIFF coaching sessions with different needs. Most unemployed and low-wage earners were interested in learning about employment opportunities or career changes that would improve their income. In contrast, employees who had recently received a pay raise or knew they would receive a raise soon came to the sessions to better understand how increased income would impact their public assistance benefits and review a long-term financial trajectory.

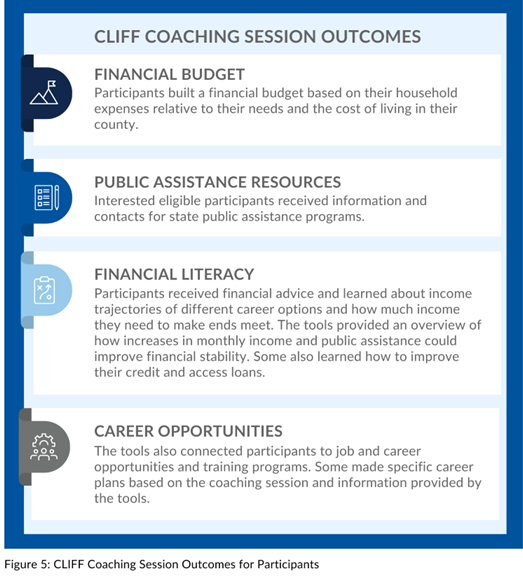

- CLIFF coaching sessions provided a menu of resources to meet these needs. Ninety percent of participants had a plan or next step at the end of their CLIFF coaching session. Services provided at coaching sessions included financial budgeting, learning about eligible public assistance programs, improved financial literacy and planning, and exploring career opportunities.

- Housing and health insurance are areas where support is most needed for participants experiencing increased income.

Recommendations for Implementing the CLIFF Program in the Workplace

The pilot program evaluation highlights strategies that employers can use to implement the CLIFF tools in the workplace. Some key strategies include:

- Invest in ample training. Training facilitators (i.e. coaches) is important to guarantee efficient use of the CLIFF tools. Employers should ensure that facilitators who will be using the tools with employees are well trained and informed, not only on the CLIFF tools and outputs but also on community resources and ethics (informed consent, confidentiality).

- Establish trust with employees first. To do so, consider implementing programs internally where relationships already exist. It is also important for coaches to share the benefits and to be transparent about how personal information is being used and protected before asking personal questions.

- Provide a self-assessment alternative with optional assistance. This option allows maximum flexibility and confidentiality for employees who are uncomfortable disclosing their personal information to a coach.

- Understand employee needs and goals to know which tool is right. Atlanta Fed provides a suite of CLIFF tools. Employers should use their established relationships with employees to first discuss employees’ needs and goals and then use this information to decide which CLIFF tool(s) are most appropriate and useful for the employee, department, or organization as a whole.

- Use the tools when they are most needed. There are certain situations when employees may be more vulnerable to, or most impacted by, the benefits cliff. These include when a person changes jobs, when a child ages out of benefits, and when an employee gets a raise.

Additional Opportunities for Employers

Beyond the CLIFF Tool, employers can take other actions to eliminate the benefits cliff problem among their workforces. Examples include aligning wages with the Living Income Standard (NC Budget & Tax Center), allowing flexible working times and spaces, providing advance pay for emergencies, and advocating for policies that would mitigate the impact of benefits cliffs on workers. For a list of other alternatives for employer, visit benefitscliffcommunitylab.org.

Acknowledgments

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Authors:

Report: Mecca Howe, PhD, UNC Charlotte Urban Institute

Executive Summary: Bridget Anderson, MPH, UNC Charlotte Urban Institute

UNC Charlotte Urban Institute + Charlotte Regional Data Trust Reviewers:

Asha Ellison, MS

Bridget Anderson, MPH

Jenny Hutchison, PhD

Khou Xiong, MPH

Lori Thomas, PhD

Sydney Idzikowski, MSW

Commissioned by:

Goodwill Industries of the Southern Piedmont

Special Thanks to:

Angelique Gaines, MA, UNC Charlotte Urban Institute

Samantha Schuermann, UNC Charlotte

Justin Taylor, Goodwill Industries of the Southern Piedmont

Employees and job seekers who participated in the evaluation

Employers and participating sites: Atrium Health, Common Wealth Charlotte, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Goodwill Industries of the Southern Piedmont, Goodwill of North Georgia

Goodwill Industries of the Southern Piedmont is a nonprofit organization that connects people to opportunities to find gainful employment and meaningful work. Through its 35+ retail stores, the Goodwill Opportunity Campus, and partnerships with employers and other organizations, Goodwill builds pathways for members of the community to uncover their passions, enhance their skill sets, and achieve more for themselves and their families—creating a brighter future for all.

The UNC Charlotte Urban Institute is our region’s applied research and community outreach center. We seek solutions to the complex social, economic and environmental challenges facing our communities. We engage expertise across a diverse set of disciplines and life experiences to curate data, conducting actionable research and policy analysis that helps us make better decisions that benefit all of us.

What is the Benefits Cliff?

A benefits cliff occurs when “an increase in someone’s pay triggers a greater loss in public assistance” (Goodwill Industries of the Southern Piedmont, n.d.). The loss of this public assistance is like dropping off a cliff because the decline in benefits is steep rather than gradual once a household exceeds certain income levels. Although an individual and their household receive more income, it is often not enough to offset the amount lost in public assistance benefits. So, the benefits cliff can lead to an increase in economic instability and financial insecurity for earners.

In North Carolina, the median annual earnings for full-time wage and salary workers is around $47,602 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2024). This is lower than the Living Income Standard (LIS) which refers to “what it takes to make ends meet with no financial cushion against emergencies like the loss of a job or illness” (NC Budget & Tax Center, n.d.) for multi-person households. The LIS for one adult with one child is $50,530 annually in North Carolina. For a household with two working adults and two children, the annual LIS is $69,270, or $16.75 per hour for each working adult. The North Carolina LIS is 2.5 times the federal poverty level and more than two times the minimum wage. In Mecklenburg County, the LIS is higher; a single parent with one child must make $59,620 a year and a family of four must make $79,490 annually, or at least $19 an hour for each working adult, to afford basic needs like food and housing.

Public assistance benefits are based on household size and total household income. For most programs, households are eligible for assistance if their total household income is no more than two times the poverty level. Once the household income surpasses the eligibility cut-off, they can no longer participate in the program (see Figure 1 for an example) and the supplemental assistance goes away. This is the benefits cliff.

The severity, or “steepness”, of the cliff varies by assistance program. Some programs have strict income cut-offs with little-to-no transitional support while others have more gradual reductions in benefits. In the United States (U.S.), those making around $13-$17 per hour, or up to $60,000 per year, are most vulnerable to the benefits cliff (Chiarenza, 2022; National Conference of State Legislators, 2019). Families with children and higher living costs, especially those needing childcare services, are also at greater risk of falling into the benefits cliff with slight income increases. The loss of childcare assistance alone can push households below the break-even line—the threshold where income meets living costs without any buffer (Ballentine et al., 2022; National Conference of State Legislators, 2019; Roll & East, 2014).

When someone experiences the benefits cliff, their income may be too low to afford living expenses but is too high to receive supplemental assistance. So, individuals or households fall into a valley of economic insecurity. This means there is no financial cushion for savings or emergency-related expenses as they live paycheck to paycheck. Families may rely on credit and loans, especially when faced with unexpected costs such as a medical emergency, further pushing them into debt and financial instability.

These burdens, despite increased income, keep individuals and their families from moving up the economic ladder–a phenomenon known as economic mobility. Economic mobility refers to “people’s ability to improve their economic status over the course of their lifetimes. Economic mobility requires access not only to income, assets, training, and employment but also more intangible resources like power — the ability to make choices for yourself and influence others — and social inclusion” (Acs et al., 2018). Economic mobility is important for ending the cycle of poverty and is associated with health benefits and furthering educational and professional opportunities (The Bell Policy Center, n.d.).

Economic mobility has benefits for employers, too. It is associated with greater revenues and inputs into the local economy. When employees earn a living income standard and have economic security, employers see reductions in turnover and absenteeism, improved health and productivity of their employees, and a decrease in overall labor costs associated with less overtime and turnover (Fairris et al., 2015; Zeng & Honig, 2017).

How does the benefits cliff impact employers?

Low-wage employees face difficult decisions regarding career advancement/professional development and qualifying for public assistance necessary to meet their basic needs. Fear of losing public benefits, because of the loss of basic support, can keep individuals from accepting more work hours, pay raises, or promotions (Joseph, 2018; Roll, 2018; Roll & East, 2014). Workers often must make trade-offs such as refusing a promotion or full-time employment to maintain access to subsidized health insurance and limit the costs of childcare, transportation, and income-based housing (see Figure 2: Sally’s Story for an example).

Because employees fear they won’t be able to care for their families if they lose public benefits, employers often lose experienced labor without any knowledge as to why. Essentially, the benefits cliff can prevent workforce development and keep employers from meeting their workforce needs. It may be difficult to fill important roles or prevent employee turnover (Cleveland Fed, 2023).

What are the CLIFF Tools?

In response to benefits cliffs, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta designed the CLIFF suite of tools (Atlanta Fed, n.d.-a). CLIFF stands for Career Ladder Identifier and Financial Forecaster. The CLIFF initiative is part of their Advancing Careers for Low-Income Families program which aims to “develop tools that support community and state efforts aimed at advancing family economic mobility and resilience, meet the talent needs of businesses, and ultimately contribute to a healthy economy” (Atlanta Fed, n.d.-a).

The tools provide useful information for low-wage earners considering financial and career decisions. They may ultimately help individuals avoid or mitigate the benefits cliff when a shift in their employment leads to higher wages.

The tools show the interactions of public assistance benefits, taxes, and tax credits with career advancements and different income levels (Atlanta Fed, n.d.-b). The suite includes the:

- CLIFF Snapshot: compares an individual’s current financial situation to alternative scenarios to show how an increase in monthly income and/or public assistance may increase financial stability.

- CLIFF Dashboard: projects income and public assistance benefits over 20 years based on a career or income change and provides the minimum monthly net income necessary to meet one’s basic needs.

- CLIFF Planner: provides a more detailed map of a chosen career path including a plan for education and employment, long-term financial projections, and a customized budget.

Coaches can use the quick start guide (Atlanta Fed, n.d.-c) to see which tool best suits a participant’s needs. The minimum budgets provided are based on the Household Survival Budget created by United for ALICE (Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed) and based on estimates for the cost of housing, childcare, food, transportation, health care, technology, taxes, and a 10% buffer for miscellaneous expenses (United Way of Northern New Jersey, 2023). The tool can also be customized to individual employer career-tracks.

What is the Benefits Cliff Employer Pilot Program?

The Benefit Cliff Employer Pilot program examines the financial implications of wage increases and seeks innovative solutions to lessen the impact of the benefits cliff on economic growth and mobility for lower-wage earners. The pilot includes employers from different sectors using the CLIFF tools developed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. Participating organizations include Goodwill Industries of the Southern Piedmont (GISP), Goodwill of North Georgia (GNG), Atrium Health (Atrium), and the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta (Atlanta Fed). Each employer identified a set of activities that incorporate the CLIFF tools and strategies for implementing the activities in the context of their working environments.

Employer Pilot Program Evaluation

Little research has been conducted on the impacts of employer-driven programs to mitigate the burden of the benefits cliff among employees. Goodwill Industries of the Southern Piedmont teamed up with the Charlotte Urban Institute (Institute) at the University of North Carolina Charlotte to evaluate how employers and service agencies can use the newly developed CLIFF tools to understand the impacts of the benefits cliff among employees and design interventions. To answer these questions, the Institute investigated the program strategies and outcomes of the four employer sites: Goodwill Industries of the Southern Piedmont, Goodwill of North Georgia, Atrium Health, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. Three sites implemented CLIFF coaching sessions with employees or job seekers. Coaching sessions were facilitated by “coaches” who were trained on the CLIFF tools. The activities and outcomes of the coaching sessions varied among the employer sites, but all sessions implemented at least one of the CLIFF tools.

Specifically, the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute explored:

- who participated in the program activities

- the outcomes of the employer-pilot program activities for employees and employers

- how the benefits cliff has impacted employees

- how the tool was used at each employer site

For more detailed information about the evaluation questions, see the research design table in Appendix C.

Evaluation Methods

The Pilot Program evaluation included data collected from two rounds of interviews and focus groups with leaders and coaches from each employer site, an online survey administered to participants after their benefits cliff coaching session, and administrative documentation of participants’ sociodemographics provided by three of the four employer sites. Two employer sites also provided notes on the session outcomes for each participant. The findings below come from a consolidation of all the data sources. The administrative data were aggregated to describe participant characteristics across the employer sites. For more details on the analysis, see Appendix C.

Outcomes

Who participated and why?

A total of 172 employees and job seekers participated in at least one coaching session as part of the Benefits Cliff Employer Pilot Program. Most were female, employed full-time, and did not have dependents[1] (Table 2, Appendix D.). Participants had worked at their jobs for different amounts of time, ranging from four months to over ten years. The median[2] individual gross income was $33,397 but differed depending on employment status (see Figure 4).

In general, Pilot Program participants earned less than what people need to live comfortably and less than most full-time salaried workers in North Carolina and Georgia. Despite having lower salaries, about half of Pilot Participants had earnings that were too high to qualify for public assistance programs such as Supplemental Nutrition Program (SNAP, i.e. food stamps), Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and Medicaid for one adult with zero children (the majority of participants). The other half of the participants were receiving or eligible for public assistance benefits.

The needs and goals of unemployed participants differed from those who were employed. Most unemployed and low-wage earners were interested in learning about employment opportunities or career changes that would improve their income. Some were seeking additional resources such as financial assistance, including public benefits programs, and help with budgeting because their current pay was not meeting their needs.

In contrast, employees who had recently received a pay raise or knew they would receive a raise soon came to the sessions to better understand how increased income would impact their public assistance benefits and review a long-term financial trajectory. Employees not receiving public assistance were primarily interested in financial planning such as improving their credit and budgeting strategies.

A common thread among all participants was the desire for economic stability. Most employees and job seekers[1] who participated in the CLIFF coaching sessions prioritized higher income and career development over public assistance benefits. They preferred to think long-term and valued the opportunity to be self-sufficient, despite the increased burden that the loss of public benefits would bring. However, it is important to consider the role of household composition and responsibilities within this finding, as the majority of participants (for whom we have data) did not have dependents.

What was gained from the CLIFF coaching sessions?

According to the survey, 90% of participants had a plan or next step at the end of their CLIFF coaching session. Specific session outcomes for employees and job seekers included financial budgeting, learning about eligible public assistance programs, improved financial literacy and planning, and exploring career opportunities.

Did the pilot program foster changes in awareness and knowledge?

Among Employees

Most individuals who were participating in public assistance programs understood that increases in their income would reduce their benefits or make them ineligible for specific programs.[1] However, the CLIFF tools and coaching sessions were still useful for participants receiving benefits– they showed current income thresholds (which change regularly) for assistance programs and specifically how much their benefits would change, in dollars, based on income adjustments. The tools provided an overview of household income after accounting for the loss of public benefits and increased taxes that participants compared to their household survival budget.

Most participants who were unaware of the benefits cliff before participating in the coaching session or survey were not receiving benefits. Some participants learned they were eligible for some public assistance programs during the CLIFF session.

Among Coaches and Employers

The employer pilot program raised awareness of the benefits cliff among employers, staff leaders, and coaches. The one-on-one approach provided a better understanding of the personal experiences of employees and job seekers and where support is most needed.

The pilot program also provided coaches and employers with useful information regarding income thresholds for various public assistance programs and household size. The coaches, specifically, became more familiar with the eligibility requirements while also learning of available programs that may support their employees or job seekers.

Lived Experiences: Impacts of the Benefits Cliff

Around 40%[2] of employees and job seekers had personally experienced the benefits cliff due to annual pay raises, promotions, or employment changes. The benefits most impacted were SNAP/WIC (i.e., food stamps), rental assistance (e.g., housing-choice vouchers, income-based public housing), earned income tax credits (EITC), and healthcare assistance (e.g., Medicaid, subsidies).

Not only did income increases result in benefits cliffs, but they were also associated with higher living expenses including increased income taxes. Many experienced increased rental costs related to income-based housing or the loss of housing assistance altogether. The loss of Medicaid or healthcare subsidies meant participants had to pay more for health insurance.

In general, the increased income was not enough to make up for the large deductions or complete loss of public assistance paired with increased living expenses. Some participants became less financially secure and economically mobile after their incomes increased. Across the sites, the income increases did not provide financial stability if they did not meet the Living Income Standard for the area and household. Additionally, those most impacted by the benefits cliff and related challenges were not the lowest-income earners but those whose pay had increased to $15/hour or more.

The degree of impact related to household income changes (i.e. steepness of the benefits cliff) varied by public assistance programs and households’ needs. Some programs like Medicaid, SNAP, and housing assistance programs were associated with steep declines in monthly benefits or an abrupt and complete loss of assistance. Childcare subsidies and EITC, on the other hand, had more gradual reductions due to higher income eligibility limits.

Housing affordability was the biggest challenge that participants discussed with coaches. Many participants struggled to pay rent due to regional increases in housing prices. For those whose income increased, some were forced to change their living situation (e.g., find roommates, live with family, change properties) due to the structure of income-based housing or the loss of housing vouchers which led to higher rent.

Concerning health insurance, many who lost access to Medicaid or federal health insurance subsidies could not afford their employer’s insurance options or income-based public healthcare benefits. This was particularly relevant for participants with dependents.

Childcare cost was not a primary concern for participants, and childcare assistance was the least impacted among the benefits reviewed. This may be related to the small percentage of participants who had children (around 34% for those whom we have this information). Additionally, North Carolina’s public childcare assistance program allows families to continue participation until their income is more than 85% of the state median household income (NCDHHS, 2024).

Employer-Specific Pilot Program Activities and Outcomes

Each employer site implemented its own programming and activities. The graphic below describes employer-specific program activities, outcomes, success strategies, next steps, and recommendations for improving the program.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta used typical wage ranges for certain jobs to test hypothetical situations and understand the impacts that income/career changes might have on access to public assistance benefits eligibility and allotment. The major takeaway was that the benefits cliff also impacts employees beyond entry level, specifically when jobs have similar starting salaries. As a result of these findings, the Atlanta Fed hopes to better understand how changes in compensation could impact employees’ public benefits and whether potential enhancements could make a difference. Ultimately, this information raises awareness and not necessarily for compensation decisions, which are largely based on market standards.

Atrium Health teamed up with Common Wealth Charlotte for their pilot program. They promoted the program to employees in their environmental team and Help Now program, and interested employees were referred to Common Wealth. Common Wealth financial coaches used the tools for one-on-one financial advising sessions and provided employees with individualized financial reports and planning. All employees were looking for ways to improve their financial security.

Goodwill Industries of the Southern Piedmont implemented the tools during personal coaching sessions with employees in the Goodwill Pathways Program. During the sessions, coaches and employees explored income trajectories, potential losses in public assistance benefits, and available assistance programs for those who were eligible. The pilot program highlighted that more than 40% of employees had experienced, or would soon experience, the benefits cliff. Despite annual pay increases, most employees in the program struggled to pay for necessities like food and housing.

Goodwill of North Georgia used the tools during career counseling sessions with job seekers who came to the Goodwill Career Center. They showed job seekers various career opportunities and how associated salaries may impact their public assistance benefits. They also used the tool to show the steps to reach career goals including training programs and educational pursuits. It was clear from these interactions that job seekers prioritized better incomes and long-term financial stability over public assistance benefits.

Application

Employer sites are using the findings from the pilot program evaluation to create and/or advocate for solutions to the benefits cliff issue among employees. Goodwill Industries of the Southern Piedmont and Goodwill of North Georgia plan to continue using the CLIFF tools with employees and jobseekers and expand the program to include more sites and employment specialists (e.g., Navigators and job trainers). Atrium Health is considering how the tool can be used by Atrium staff to more directly support employees.

[1] 61% of survey participants said they would accept a promotion or raise despite the potential loss of assistance benefits; 58% of employees in the GISP Goodwill Pathways Program accepted a pay raise even though their benefits were impacted; 81% of participants from the Goodwill of North Georgia Career Center were looking for employment opportunities or a career change that would improve their financial situation (e.g., income).

[1] These findings stem from a combination of data including the survey data and qualitative data from interviews/focus groups and notes provided by GISP. Among participants who took the survey, 60% of those who were unaware of the benefits cliff were not receiving public assistance benefits, while nearly 60% of those who were aware of the benefits cliff prior to the pilot were receiving public benefits at the time of the survey.

[2] 42% of employees in the GISP Goodwill Pathways Program; 38.5% of survey participants receiving benefits.

Lessons Learned from the Benefits Cliff Employer Pilot Program Evaluation

The Benefits Cliff Experiences and Impacts

- Most Pilot participants likely struggle financially because their incomes are below what they need to meet basic needs, but often just above the income limits for most public assistance programs.

- The effects of increased income (e.g. receiving a raise) differ among public assistance programs. Some have strict income limits that cause significant or total loss of support, while others allow for a smoother transition because some support remains.

- Higher income is often associated with increased living expenses including higher taxes, increased rent, unsubsidized health insurance, and a larger portion of income needed for food.

- Despite losing public assistance benefits and higher expenses, most participants would accept a promotion or raise. Participants valued self-sufficiency and income over public assistance.

- Housing and health insurance are areas where support is most needed for participants experiencing an increased income.

For more discussion of these findings in relation to context and literature, see Appendix G.

Best Practices for Employer Utilization of the CLIFF Tools

There are direct and indirect action opportunities for employers to help mitigate the benefits cliff among their employees. One immediate option is to use the CLIFF tools to help employees understand the impacts of income and career changes as well as provide employers with insight into where support is most needed. The tools can show which specific benefits are impacted, how much, and what income employees need to get over the benefits cliff and become economically secure.

The pilot program evaluation highlights strategies that employers can use to implement the CLIFF tools in the workplace.

Ample Training

Training facilitators (i.e. coaches) is important to ensure efficient use of the CLIFF tools. Because of the nature of economics and public assistance programs, the tools ask for a lot of information and have multiple steps. They produce an array of information that may be difficult to understand without training. Employers should ensure that CLIFF tools facilitators receive thorough training not just in the tools and their outputs, but also in ethical practices. This training should cover the importance of obtaining consent, maintaining confidentiality (including proper data management), and fostering respect through cultural awareness. These trainings will ensure employees and their personal information are protected and treated appropriately.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta provides training resources including demos of the CLIFF tools (see sources by Atlanta Fed below in the works cited list). After training, facilitators should practice using the tools in various scenarios to become proficient with the programs and informational products.

Establish Knowledge and Connections with Public Assistance Programs and Agencies

Before implementing the CLIFF tools among employees, employers and facilitators should have training on state and local public assistance programs and resource-support organizations. This knowledge will ensure that employers can guide employees to resources when needed. Employers should also establish connections with public assistance agencies and local organizations in which employers explain the CLIFF tools program and learn the best contact strategies (e.g., who to contact and how) when employees need assistance.

Establish Trust with Employees First

The tools ask for a lot of personal information including some items that employees may feel ashamed to share (e.g., public assistance, financial burdens such as debts). Facilitators must establish a trusting relationship with the employee before implementing the tools to ensure the information provided is accurate and the tools are used in ways that best serve the employee and their needs. Some ways to establish trust and rapport include:

- Implement programs internally where relationships already exist. Staff leaders and representatives likely already have a relationship with employees. Utilizing these established relationships can reduce the time needed to build the trust and confidence necessary for creating a new connection. If possible, employers should use the tool in-house rather than referring employees to another business or organization where there is no existing relationship.

- Increase awareness and normalization of the benefits cliff and services by building it into existing programs such as new hire onboarding or annual training workshops.

- Share the motivation and be transparent before asking personal questions. Explaining what the tools do, why they are used, and how information is used within the tool(s) will help employees understand the reasons behind the questions and the benefits of the tools and programming. Employers should be transparent about how they use the tools and why and explain how they will protect employees’ information and address their concerns. Facilitators can share their screens so employees may see the questions, what information is being added, and the outcomes of the tools.

Understand Needs and Goals to Know Which Tool is Right

Employees have different needs that reflect various goals depending on their personal and household situation. Those receiving public assistance benefits are likely interested in learning how they will be impacted by income changes. Those not receiving benefits may be more interested in alternative support and career development. Employers should use their established relationships with employees to first discuss employees’ needs and goals. Then, use this information to decide which CLIFF tools are most appropriate and useful for the employee.

Provide a Self-Assessment Option with Assistance when Desired

No matter the relationship between the employee and facilitator, some individuals may not be comfortable providing personal information and discussing income-related challenges. For these employees, a self-assessment alternative with optional assistance should be provided. Employees interested in self-assessment can participate in the training (as facilitators do) and request assistance if needed. Employers should also provide the optional opportunity for employees to discuss the tools’ outputs with employers, including areas where they may need support.

Use the Tools When They are Needed Most

There are situations when employees may be more vulnerable to, or most impacted by, the benefits cliff. Employers should use the CLIFF tools at the following times to best support employees when interventions are most needed:

- When an individual changes jobs: a new job may bring higher income and impact assistance benefits. In addition, a new position could bring on increased expenses related to transportation and childcare. Plus, most employees will experience a delay in receiving their first paycheck. For individuals living paycheck to paycheck, this delay can become a significant financial burden. Employees can use the CLIFF tools to help create a financial plan and budget and to find short-term assistance. They can work with employees to understand the longer-term advantages of the new position and career growth. Employers provide support by eliminating the pay delay or providing a pay advance.

- When a child ages out of benefits: WIC and Medicaid have age limits. When a child ages out of these benefits, families incur increased expenses such as having to pay for health insurance and increased food costs. In addition, childcare subsidies often stop at age six, when a child tends to begin school. After-school care may be costly, especially if a family does not qualify for low-income programs. This is an opportunity for employers to use the tool to help employees create a financial plan, budget, and access resources. Employers can also support parents by providing affordable health insurance for dependents, allowing flexible work hours or work-from-home days to reduce costs associated with after-school care and transportation.

- When an employee gets a raise: promotions, annual raises, or increased work hours can push employees over the income limits for public assistance programs and into the benefits cliff. This is a vital time to use the CLIFF tools to explore the immediate and long-term impacts of a salary increase to help employees weigh the pros and cons and think longer-term. The tools will show financial trajectories and changes in household expenses, and employees can work with workers to find solutions to the immediate burdens of losing benefits to promote career development and economic mobility.

Additional Opportunities for Employers

Employers can implement internal policies and programs that work to eliminate the benefits cliff or provide direct support to employees experiencing the benefits cliff. They can also advocate for relevant state and federal policies. Here are additional opportunities for employers to make an impact.

Pay the Living Income Standard (LIS)

An income that meets the LIS (NC Budget & Tax Center, n.d.) would eliminate the reliance on supplemental income assistance and public benefits and prevent the benefits cliff. Better yet, providing an income that meets the ALICE household survival budget (United Way of Northern New Jersey, 2023) would allow employees a financial cushion (e.g., savings and assets). This cushion supports economic security and mobility, as employees are better prepared for unexpected costs and higher expenses associated with increased income. Additionally, an income that meets employees’ needs reduces the dependence on credit cards and loans that increase debt and ultimately helps employees reach economic stability and security.

Paying an LIS also has benefits for employers. Investigations show that living-wage initiatives result in less employee turnover and absenteeism, higher productivity, and overall reduced costs for employers associated with less overtime (Fairris et al., 2015; Zeng & Honig, 2017). Furthermore, a living wage allows employees the ability to pay for health coverage, resulting in incentives for employers who offer health benefits (Bindman, 2015; Fairris et al., 2015). Access to health insurance paired with reduced stress associated with financial security and improved work-life balance (e.g., not needing to work overtime) can also lead to healthier and happier employees (Pickett, 2014).

Allow Flexible Working Times and Spaces

Allowing low-wage employees flexibility in their work schedule can reduce trade-offs between work, including career development and advancement, and life (Roll, 2018; Ruppanner et al., 2018). It can also cut expenses and reliance on public assistance programs, especially when allowing employees to work from home. Recent investigations show that working from home is the most valued employee-friendly alternative, particularly among women with young children (Mas et al., 2017). Remote work can reduce costs associated with commuting and childcare (Mas et al., 2017). It also provides more flexibility when choosing where to live, possibly reducing housing costs.

The ability to work non-traditional hours, too, can help parents minimize childcare costs such as those associated with after-school programs or daycare. Plus, flexible hours eliminate the need to use limited sick- or vacation time for tasks that must be completed during traditional working hours like doctor appointments and auto maintenance.

Studies show that flexible work arrangements have benefits for employers, too. Flexibility is a large incentive to attract and retain well-qualified employees (De Menezes & Kelliher, 2017; Mas et al., 2017; Rudolph & Baltes, 2017). Flexible work schedules have been connected to increased productivity, improved performance, customer satisfaction, and employee gratification and commitment (De Menezes & Kelliher, 2017; Rudolph & Baltes, 2017). Allowing remote work can even reduce costs for employers – U.S. employees are willing to earn 8% less to work from home because they understand the personal cost savings that this arrangement brings (Mas & Pallais, 2017).

Sponsor Income-Based Health Insurance

One-size-fits-all health benefits are not always accessible to lower-wage earners or those experiencing the benefits cliff. Offering income-based and individualized health insurance provides employees with access to health coverage they can afford. This is a large incentive for employees, especially those with dependents (Fairris et al., 2015), and could be the deciding factor between accepting a promotion or working more hours and losing public health coverage. Employers can implement the Employer Shared Responsibility Provision (part of the Affordable Care Act)(IRS, n.d.). They may also opt to cover a large percentage of private-provider premium costs so that employees pay less for coverage.

Research shows that employee-sponsored affordable health coverage attracts job seekers (U.S. Chamber of Commerce, 2022). It is associated with less absenteeism and improved employee well-being, which can increase productivity (U.S. Chamber of Commerce, 2022).

Provide Advanced-Pay or Earned Wage Access for Emergencies

Individuals living paycheck-to-paycheck and those in the benefits cliff do not have the means to save for life’s unexpected costs (e.g., car repairs, injury). Employers can provide earned but unpaid wages to employees before payday or offer an advanced-pay option that employees will make up over time. This will assist employees with stability by reducing their reliance on high-interest loans, credit cards, or private check advances (Binney, 2024; Miller et al., 2012)[1]. Earned wage access also attracts and retains employees (Binney, 2024).

It is important to note that although providing access to earned wages or pay advances may protect employees from increased debt, the benefits are solely temporary. It does not eliminate the underlying causes of financial insecurity associated with low wages and the benefits cliff (Dennis, 2023).

[1] See various guides for employers on how to offer payroll advances: employer’s guide to payroll advances by Indeed (Indeed, n.d.)); the ultimate guide for employers by Homebase (Homebase)

Offer a Savings Account

Some public assistance programs are based on net income rather than gross. A way employers can help create a bridge between public benefits and financial stability is to delay the distribution of increased income associated with a pay raise. Instead, the additional income is saved until the employee feels they can survive without public benefits. For example, if an employee receives a pay raise from $15 to $19 an hour, the employer could provide the option to save the additional $4/hour in an individualized account for a determined amount of time. This would give employees the chance to save in preparation for the benefits loss and potentially increased expenses.

This strategy is similar to emergency savings accounts linked to employer-sponsored retirement accounts like Roth (ADP, n.d.) and traditional employer-sponsored emergency savings accounts. The differences include the timing when the account is initiated, who manages the funds (employer vs bank), and the objective. With the proposed model, the goal is to provide a bridge (i.e. cushion) to help employees over the benefits cliff. Traditional emergency savings accounts are for emergencies and often have a maximum savings limit. The proposed account also keeps employees from having to withdraw from retirement funds.

Advocate for Policy Change

Some Employer support, employee knowledge, and planning won’t eliminate the benefits cliff for everyone. Employees can advocate for policy changes necessary to solve the benefits cliff issue completely. Some areas for policy interventions include:

- Increasing the minimum wage or implementing living wage policies.

- Altering the structure of public assistance benefits so that each program reduces benefits gradually rather than abruptly (i.e. provide a transitional support period).

For more ideas for employer strategies and policy, see Goodwill’s Benefits Cliff Community Lab resources (Goodwill Industries of the Southern Piedmont, n.d.).

Future Research Recommendations

Ensure Representative Participation and Data, Including Individuals with Dependents

A limitation of this analysis was the lack of data regarding household size and composition which led to the overrepresentation of individuals without dependents. Future research should ensure the standardization of data across all employer sites/programs and the collection of data related to household characteristics. Employees and job seekers with dependents may have different experiences and needs that ultimately lead to different preferences and choices. Ensuring quality and representative data collection will improve the validity of the analysis and results, particularly the takeaways and recommendations.

Ask Those Experiencing the Benefits Cliff for Solution Recommendations

Individuals experiencing the benefits cliff are experts on the issue. They know what solutions would be most impactful based on their needs and experiences. Future research should focus on underscoring the voices of those with lived experiences and capturing their recommendations including opinions about where support should come from, when, and who should provide it. This research would also capture variation in needs across different sociodemographic groups (e.g., household sizes and makeup) and spaces (e.g., rural versus urban). Altogether, the information would better inform recommendations for programs and policy.